Why I Might Read The Sense of an Ending

The short answer? Considering it won The Man Booker (in 2011), it might be more reasonable to wonder why I wouldn’t read The Sense of an Ending. But when it came out, a few friends said they’d been disappointed by it. One friend hated it. For better or (possibly) for worse, I tend to skip prize-winning books written by men in favor of other books written by women. And so I skipped The Sense of an Ending.

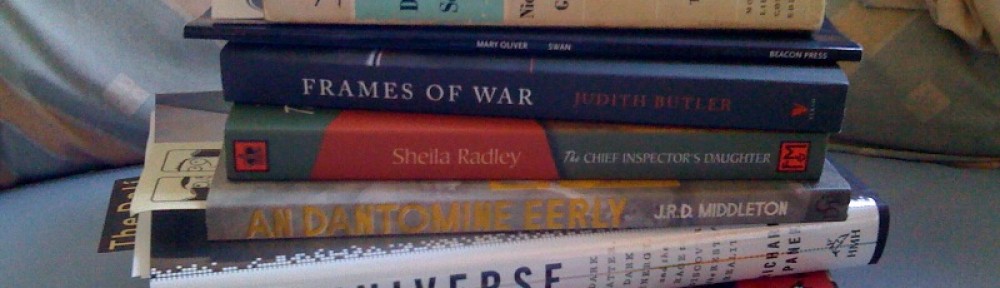

But now I might read it. I’ve been staying in a house filled with someone else’s library. Like most things here, the books are well-chosen, eclectic and strongly individual: preferences for Flannery O’Connor, Gabriel García Márquez, Annie Dillard, Robinson Davies, and O. Henry prize-winning short story anthologies. There are also several paperback novels by Julian Barnes (who wrote The Sense of an Ending). I finally got around to reading one of them and it impressed me. That begins the long answer.

“Staring at the Sun” by Julian Barnes

Staring at the Sun was published more than 20 years ago, in 1986. Before I checked the publication date, I would have guessed the book was more recent than that. Not that 1986 is so terribly long ago—this book just manages to feel quite contemporary as its story openly and skillfully travels forward from the past. Staring at the Sun follows the life of one woman, Jean Serjeant, beginning with her 1920s childhood adventures caddying for her charming, lonely, oddball Uncle Leslie, following her late-adolescent fascination with Sergeant-Pilot Tommy Prosser, a grounded RAF officer billeted with her family and then her late-WWII marriage to a police officer named Michael.

After twenty years of childless, largely loveless, and in her eyes, fairly typical conjugal partnership, Jean unexpectedly becomes pregnant. When her husband asks her what she plans to do, she replies “Oh, I’m going to have the baby and leave you…But I expect I’ll leave you and then have the baby. I expect I’ll do it that way around.” And leave him she does, raising her son, Gregory, in a state of perpetual flight from one low-rent apartment building to another. Once he is safely installed in self-sufficient adulthood, Jean continues to fly, traveling to China, the Grand Canyon, wherever she can manage, almost always alone. Her observations about the world are keen and intelligent and humorously matter-of-fact and her curiosity is unending. She’s a wonderful protagonist.

The novel wraps up as Jean Serjeant, now nearly 100 years old and living in a sci-fi-esque, eerily prescient, 21st century (where most information is instantly available via computer and you can apply to speak to TAT, a restricted-use area of the universal database whose acronym stands for The Absolute Truth), after a life spent thinking about how to live, begins to think about how to die. Even this has been made “easier” in the first years of the imagined new millennium.

This book was funny, smart and exquisitely well-crafted. The most compelling part of the novel for me was Jean’s relationship to a man she barely knew, the pilot, Tommy Prosser. As Barnes suggests through the delicate similarity between Jean’s surname (Serjeant) and Tommy’s rank (Sergeant), these characters share a deep, imperfect sympathy. Or at least, Jean shares a deep sympathy with her memories of Tommy Prosser. “I’ll tell you the most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen,” he says to Jean one morning in her kitchen, and then he describes for her an ordinary miracle neither of them will ever forget: flying back from France across the English channel one morning at dawn, he watched the sun rise in the east. Aware of how visible his black-painted plane was in the light, he climbed back into darkness and then dropped into such a fast dive that his speed drove the sun back beneath the horizon. As he approached England, it climbed out of the darkness for a second time. Two dawns on the same day. Strange, solitary beauty in the midst of a war full of horrors and loss.

Two dawns—the sort of thing you can’t really see if you obey the prohibition not to stare at the sun, or if you follow other rules that keep you grounded in normalcy. But the moment you disobey, you realize that some facts and impossibilities are little more than matters of popular habit and agreement. This is a book about Jean’s curiosity teaching her to disobey the major rule of her existence (“to obey”) and about everything she sees after that. It is also a novel about the rules that most concern us—you know, the ones about life leading inevitably to death—and how to go about living within them. It’s not a life-changing book, but it was a very good one. Good enough to get me to read something else by Julian Barnes. Like maybe The Sense of an Ending.