I haven’t read The Complete Works of William Shakespeare cover to cover, but I’d hazard a guess that The Winter’s Tale is one of the strangest of Shakespeare’s plays. Its first three acts go over like tragedy, the fourth act is full of ridiculous comedy, replete with idiot farmers, disguises, raunchy country dances, and copious amounts of alcohol, and the fifth and final act is nothing short of bizarre, magical, and completely unlike any other final act of Shakespeare’s I’ve ever read. A lot of people don’t like The Winter’s Tale, but I’m oddly fond of it. And the production of it I saw last night, put on by Shakespeare & Company in Lenox, MA, only made me like it more, even though, at the same time, it confirmed all of my feelings about what a funky play it is. No wonder it’s so often referred to as a “problem play.”

As the action opens, Leontes, King of Sicilia, begins to suspect that his boyhood companion and best friend, Polixenes, King of Bohemia, is having an affair with his pregnant wife, Hermione. Furthermore, he suddenly, and on the basis of very scant evidence, decides that the baby is in fact Polixenes’, not his own. His reaction? He asks his servant, Camillo, to poison Polixenes. Instead, Camillo warns Polixenes, and then flees with him back to Bohemia. Their flight just spurs Leontes’ anger, and he imprisons Hermione despite the protests of all the gentlemen in his court, and of the outspoken noblewoman Paulina (my favorite character). To assuage their fears that he is punishing an innocent party, and to refute the almost unspoken accusation (brilliantly not quite leveled at him by Paulina) that he is a tyrant, he sends to the Oracle at Delphi, to confirm Hermione’s guilt.

Meanwhile, in prison, Hermione has her baby, safely delivering a daughter. When shown the child, Leontes is unmoved, and sends his servant, Antigonus (Paulina’s husband) to take the baby to a faraway land and leave it in the middle of nowhere, unprotected, to live, or as seems far more likely from a common-sense, non-Shakespearean-problem-play point of view, to die.

When the Oracle’s message arrives, and declares Hermione unequivocally innocent, instead of relenting, Leontes refuses to listen, and condemns Hermione to die. And in an instant, thunder strikes and tragedy arrives: his young son, Hermione’s first child, Mamillius, dies. Hermione, still weakened from giving birth to her daughter, collapses, and is carried offstage. Moments later, Paulina reappears, berating the King for his crimes, and near crimes, and she reveals that Hermione is dead. Leontes is a broken man; immediately filled with profound remorse, he repents. Did I mention that the Oracle predicted that if Leontes didn’t free Hermione, Bohemia would go without an heir until he was reunited with his daughter (who he’d already sent to die on some far shore of Sicilia)? Right, well, the Oracle said that, and now that his son and wife are dead and his daughter lost, he finally believes it. And he’s miserable. Seems pretty tragic, right?

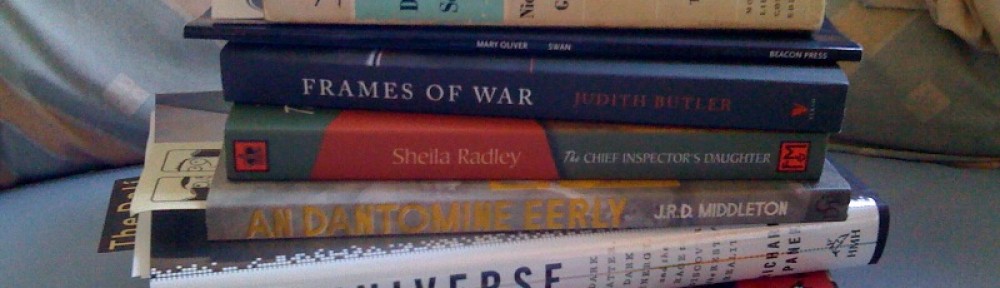

Leontes (Jonathan Epstein) and Hermione (Elizabeth Aspenlieder) in the Lenox Shakespeare & Company's production of "The Winter's Tale," by William Shakespeare. Credit: Kevin Sprague

Cut to the very end of Act Three…Antigonus leaves the baby girl somewhere in the “deserts of Bohemia” (but near the shore, because he’s not far from his ship…geography isn’t of the utmost here). He names her Perdita, leaves her with money, and a scroll revealing her parentage. And then, in perhaps the most famous stage direction in all of Shakespeare, Antigonus “exits, pursued by a bear.” And for everyone but Antigonus, who rather gets it from the bear (and all those left back in mourning in Sicilia), comedy ensues. 16 years pass between the end of Act III and the beginning of Act IV, and we find young Perdita, believing herself to be a farmer’s daughter, in love with Florizel, prince of Bohemia, the son of the once-suspected Polixenes. There’s lots of dancing, lots of drinking, lots of sexual puns, many disguises, a rascal named Autolycus, and some genuinely hilarious scenes.

And then there is Act V, back in Bohemia. I won’t even go there. If you’ve kept up this far, you should just read the play yourself! Suffice it to say, the ending of this play caught me a bit by surprise the first time through. Maybe because I thought I was reading a tragedy, and then thought it was a comedy, and then in Act V, I got thoroughly confused. This play reminds me a bit of an idea a friend of mine and I had, of creating films that start out fully enmeshed in the language and conventions of one genre (say, romantic comedies) just to switch, at some undisclosed and wholly random moment in the middle, to a completely different cinematic style (cheap slasher flick, or brainy foreign mystery, for example). All in all, it’s a pretty fun ride, even if you’re still a bit disoriented at the end.

When I see Shakespeare, instead of simply reading him, some things become much clearer to me, and other things pass me by completely. I inevitably lose some of the language, no matter how familiar I am with the play, because I get caught up pondering certain lines which strike or surprise me when I see them live, perhaps because the delivery of the actor is spectacular or unusual, or simply because the lines leap differently out of mouths than they do off the page. All I want from a live production (as a minimum, anyways) is that I realize something new about the play, something I hadn’t gathered from the page. Last night’s play definitely met this expectation. I realized that despite the tragedy which fills the first three acts, the seeds of comedy are there, in Paulina’s not-so-gentle ribbing of Leontes, and thanks to the strong performance by Jonathan Epstein as Leontes, I was able to understand, a little bit, his baseless suspicions, and even more baseless accusations.

In the moment after he has condemned Hermione to death, in defiance of the Oracle’s statement of her innocence, the exact moment when thunder rings across the stage, Mamillius dies, and Hermione faints, bringing the Oracle’s prediction into reality, Leontes seems to collapse into himself. He goes from tyrannical bravado to utter remorse in .2 seconds, flat. And in that .2, I saw a man who wasn’t so much angry at his wife and best friend for believing they were screwing around behind his back, but just a man born to power, raised with power, always in power, wondering if there was actually a power beyond himself. That moment made the whole production worth it to me, because it gave me something new to think about, a new way to understand a character I’ve always found totally puzzling.

Not to bore you with more about Shakespeare, but I also saw another production in Lenox, yesterday. This one was called Women of Will, written by actress and director Tina Packer, and performed by Packer and her acting partner, Nigel Tucker. Women of Will is an investigation of the way that Shakespeare wrote his female characters, proceeding chronologically through his career. It was a bit like attending a really great, inventive and exhilarating three hours seminar on Shakespeare. (Yes I know, only I could find a three hour seminar on Shakespeare exhilarating). Perhaps the most interesting “scene” from Packer’s production was the one in which she spliced together scenes from Othello and As You Like It, to demonstrate the different fates awaiting the women in Shakespeare who, like Desdemona, attempt to act as purely feminine women, and those who, like Rosalind, disguise themselves as men in order to navigate the world. The quick changes were jarring, and powerful. Packer is extending Women of Will into a five set series, starting this fall. If you’re interested, you can find more information here.